Unpacking rare earths

Welcome to the Alts Sunday Edition

My name is Gustavo, and I publish Critical Minerals Journal. It’s an independent research publisher focused on the often overlooked (but increasingly strategic) world of critical minerals.

My research currently covers Rare Earths, Uranium, Copper, and Lithium. I’m also directly involved in developing a rare earth mining project in Brazil, which gives me a hands-on and unique perspective of the sector.

This is the first Critical Minerals Journal issue outside of CMJ, and it’s an absolute pleasure to partner with Alts (big shoutout to Stefan).

Before we get started, consider yourself already a member of our CMJ community, and please feel free to subscribe or DM me at: criticalmineralsjournal.substack.com

If you’re new to this space, skim the issue to get oriented.

If you’re getting serious about precious metals investing, read the full piece.

Let’s go

The backbone of rare earths

The familiar stories everyone gets wrong

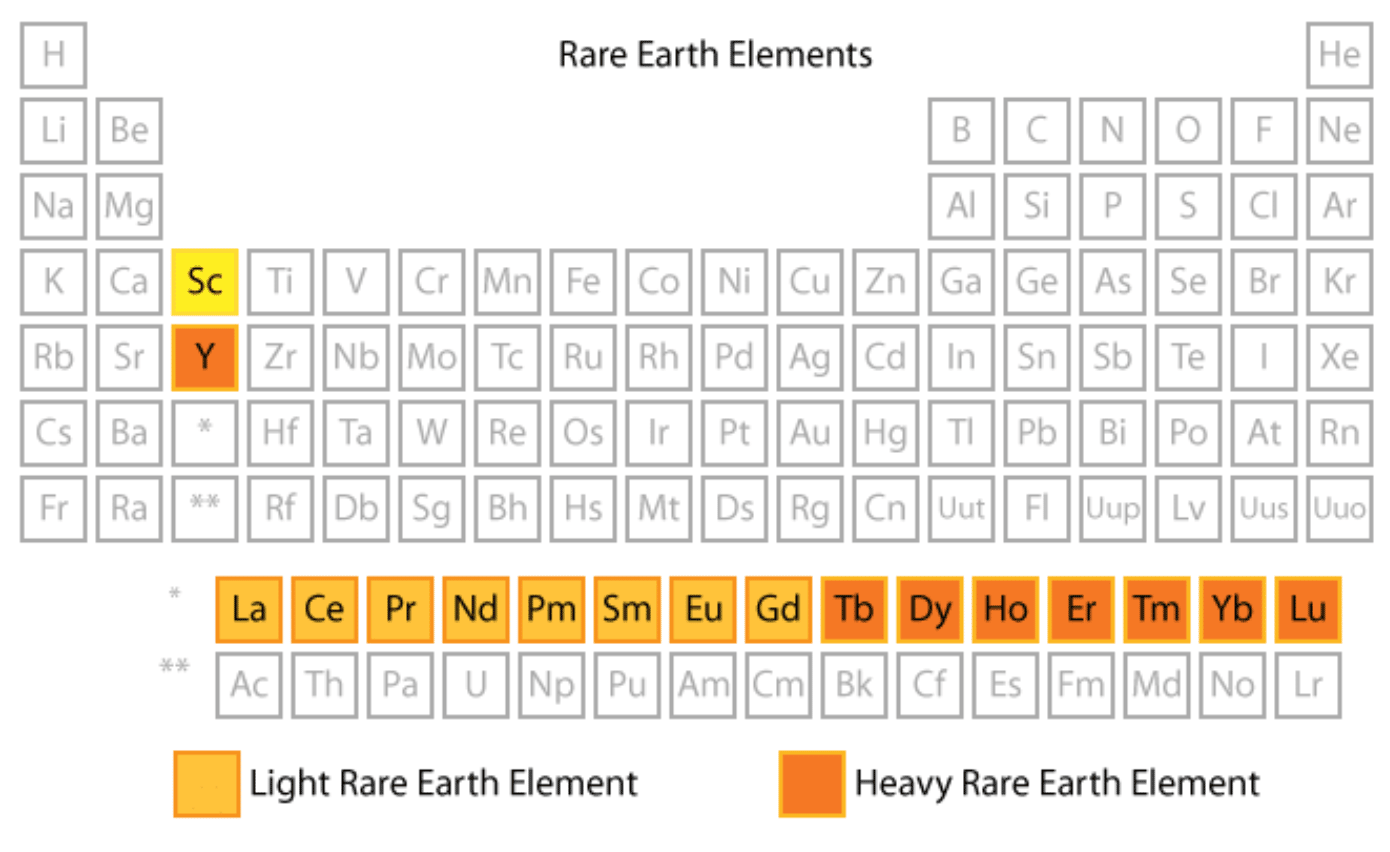

Rare earth elements (REE) are among the most widely referenced (and least understood) materials in modern industrial policy and alternative investing.

Policymakers invoke them as symbols of strategic vulnerability, and capital flows toward projects labeled ‘non-Chinese supply’ (don’t worry, we won’t get into geopolitics here).

And yet, after more than a decade of attention, the same pattern repeats: ambitious projects fail to reach steady-state production, downstream bottlenecks persist, and supply chains remain fragile despite billions deployed.

The mistake is not a lack of capital or interest. It’s a faulty mental model (and I’ll give a tool to fix it).

Rare earths are almost always analyzed like conventional mining assets: find the deposit, build the mine, produce the concentrate, and sell into a growing market.

This framing is intuitive, but deeply misleading.

Rare earth value is not created by finding rocks, but by reliably converting complex molecules into qualified products within constrained, specification-driven supply chains.

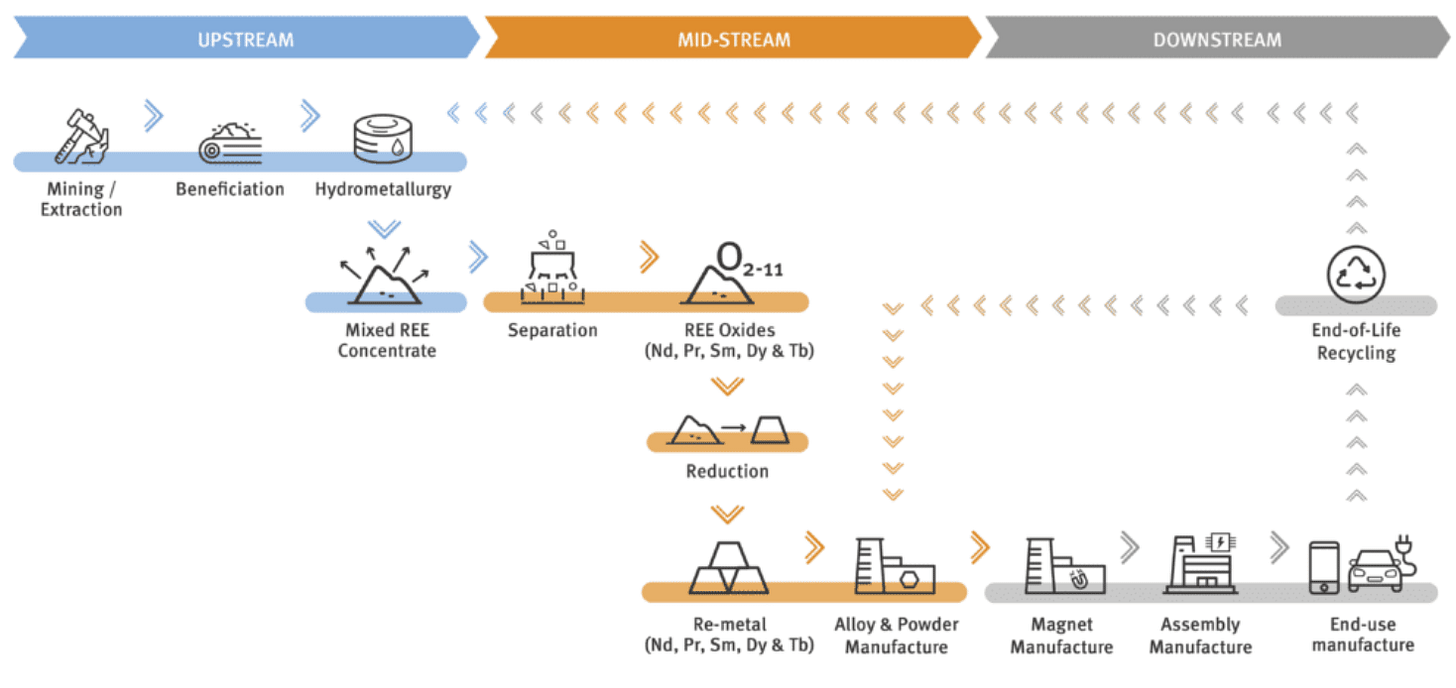

Mining is merely the opening move in a long industrial sequence where chemistry, process engineering, market access, and coordination matters far more than grade alone (often referred to as the Total Rare Earth Oxide grade, or TREO).

Until investors internalize this distinction, they will continue to misprice risk, overfund marginal projects, and underestimate why so many ‘strategic’ assets never become viable suppliers.

My goal is to explain how the system actually works and where value is really made or lost.

The dominant narrative (and why it fails)

Most rare earth discussions rest on a handful of shortcuts that feel directionally correct but break down under scrutiny.

“China controls everything”

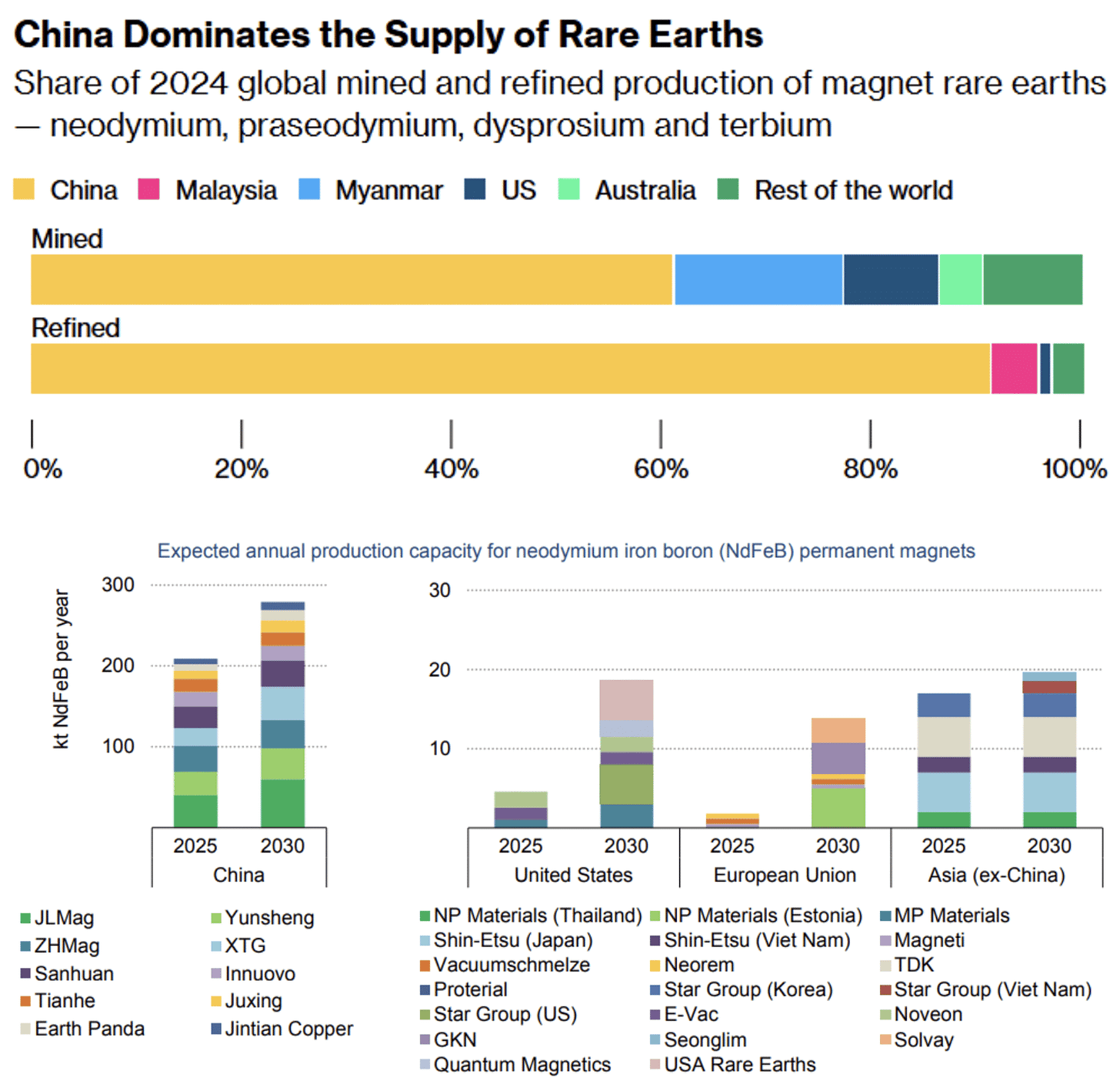

China does dominate much of the rare earth value chain, but dominance is not monolithic, it varies by product form, specification, and processing stage:

Concentrate > Carbonate > Oxide > Magnet Grade Alloy > Permanent Magnet (standard) > Custom-made Permanent Magnet

Here is a very interesting video explaining the Permanent Magnets properties and their value chain: (in the end of the day, it’s important to keep in mind the end product from REEs)

In short, treating supply as a single fungible pool obscures where bottlenecks actually sit. Here are a few extra examples:

“EVs + wind turbines drive explosive demand”

Permanent magnets are critical to modern electrification. There’s no doubt about it.

But demand is not a simple function of unit volumes! You also need to consider magnet design, platform architecture, intensity assumptions, substitution, and qualification timelines.

The demand is real, but rarely as linear as forecasts imply.

“Scarcity means any project has value”

This is perhaps the most damaging assumption. Please, never say this.

Rare earth supply is not interchangeable.

A tonne of mixed rare earth carbonate (MREC) with unfavorable impurity profiles (or even a ‘cheaper’ distribution of elements) is not equivalent to an already separated oxide, let alone magnet-grade metal.

Many projects discover too late that they are producing something the market cannot, or will not, absorb.

The common failure across these narratives is the same: they treat rare earths as a mining scarcity problem, when in reality, they are a manufacturing and coordination/supply chain problem!

In short, supply is not constrained by geology, but rather by the capabilities to refine material through a tightly coupled chain of separation, purification, metallization, and qualification.

These are critical steps where errors compound and timelines stretch.

How to evaluate REE projects

The ‘low hanging fruit’ illusion: Ionic Clays vs Hard Rock

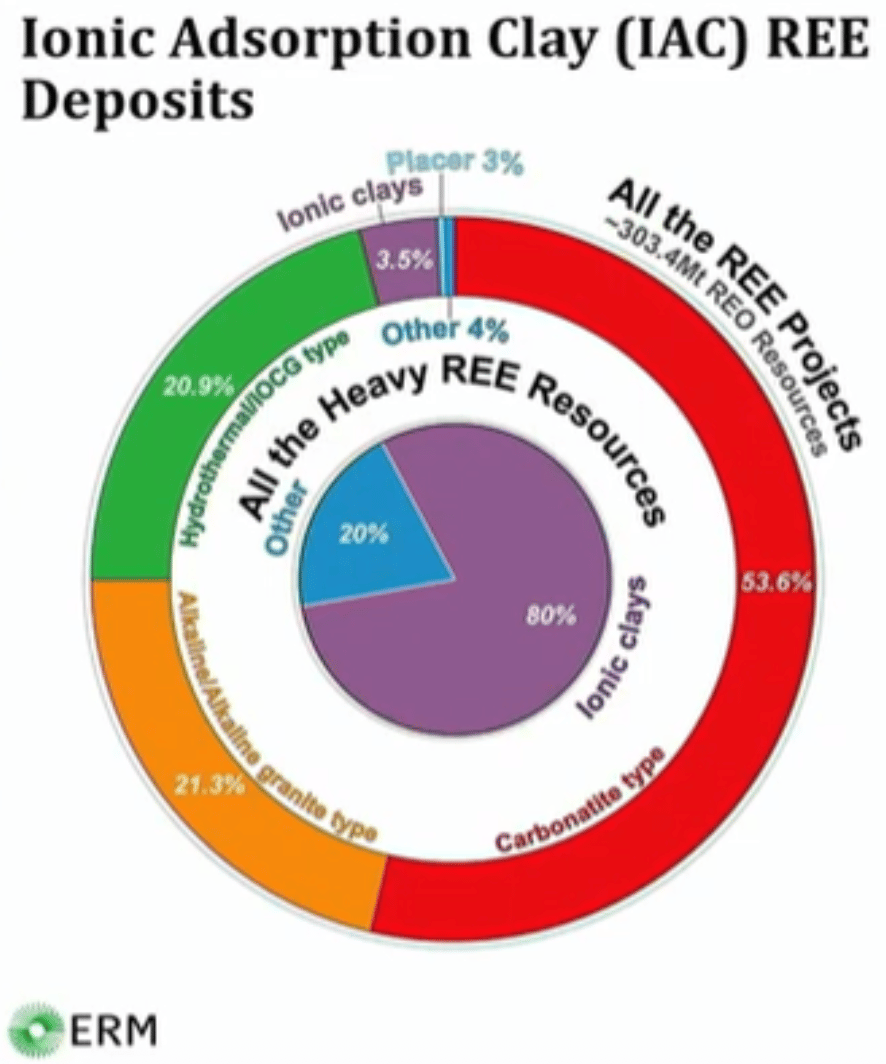

Few ideas have attracted more enthusiasm in rare earth investing than the concept of ‘low hanging fruit’ geology, particularly ionic adsorption clay. deposits (IAC)

At first glance, the appeal is obvious.

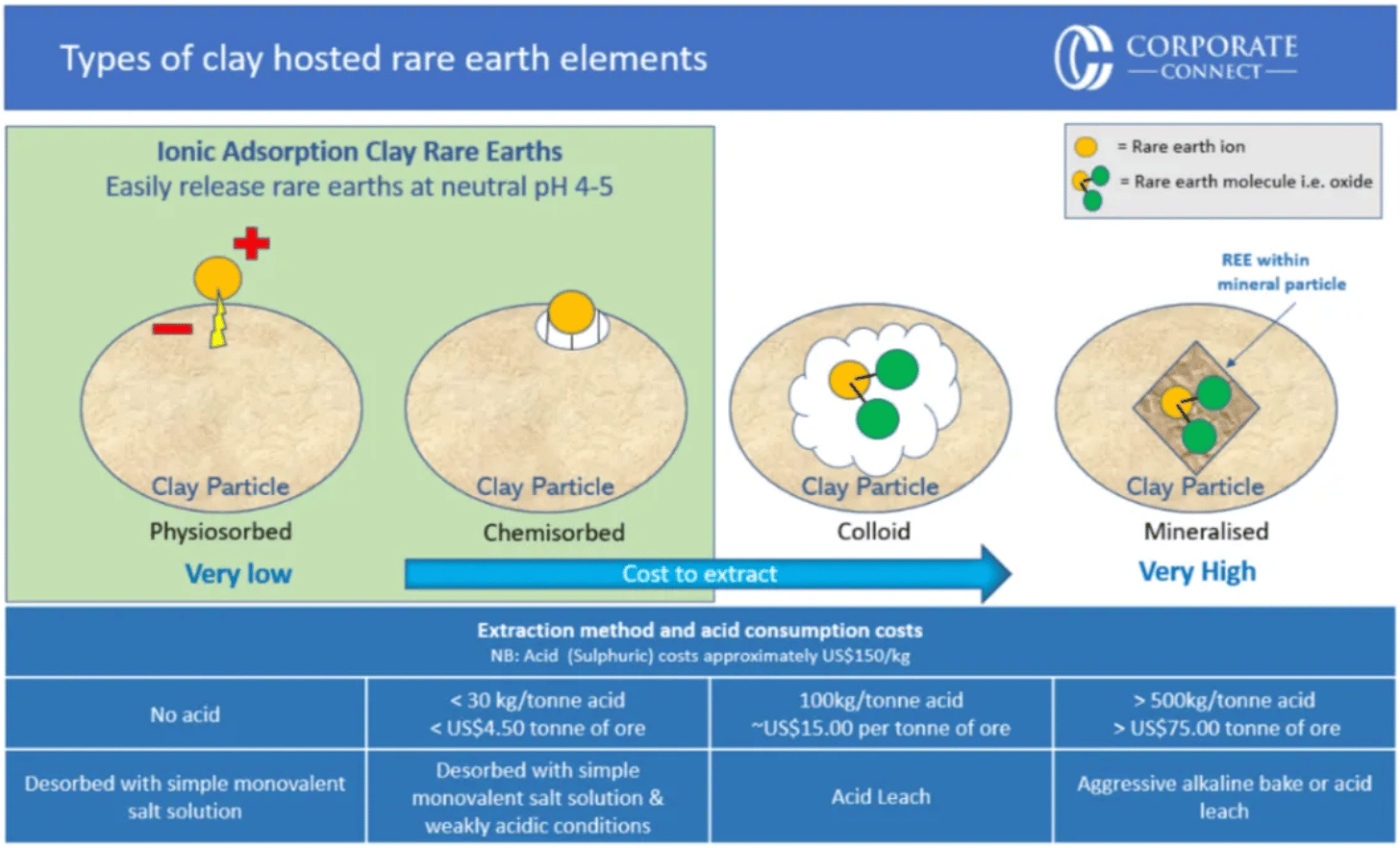

Over geological timescales, rare earth ions are naturally leached from primary minerals and become weakly adsorbed onto clay surfaces. They are not lattice bound, it’s a simple surface binding.=

Typical grades are lower compared to hard rock — often a few hundred to a few thousand ppm in TREO (total rare earth oxides).

The advantage is that, because REEs are weakly bound to clay surfaces, they are theoretically recoverable via relatively mild ion exchange leaching process.

This distinction matters. In principle, IACs allow:

Lower crushing and grinding requirements (conceptually even zero)

Ambient temperature leaching

Reduced reliance on aggressive acids

These characteristics have led many investors to assume that ionic clays are inherently simpler, cheaper, and faster to develop than hard rock projects, oversimplified as ‘low hanging fruit’.

But this assumption is incomplete!

Yes, IOC has a favorable chemistry and potentially even revenue. But its operations could be harder given the clay material you’re dealing with.

See, clays are fine grained, friable, plastic, water retentive, and operationally unforgiving (particularly for operators without prior experience!)

Grades are also low, which means:

High material throughput for modest REE output

Large solution volumes per unit of product

Tight sensitivity to recovery efficiency and reagent consumption

The weathering profiles that create IACs also introduce complexity:

Heterogeneous clay mineralogy (meaning the deposit grades and content varies throughout its body)

Variable permeability across horizons

Elevated aluminum, iron, and other competing ions (a.k.a. impurities)

Strong sensitivity to pH control

Bottom line: what appears to be a geological ‘low hanging fruit’, often becomes a high complexity operation at scale.

And this is precisely where differentiation emerges. Ionic clays aren’t bad, but they shift the risk equation from mineral liberation and cracking, to material handling, filtration and process control.

The correct mental model: Rare Earths as an industrial system

To understand rare earths, it helps to discard the mining playbook and adopt a manufacturing one.

The REE value chain looks roughly like this:

Ore (material handling) > leaching <> purification > precipitation > separation > product specification > customer qualification > offtake

(Note the loop between leaching and purification.)

Each arrow represents a potential failure point. Mining sits at the front and after precipitation, we’ll talk about it in a second.

Here’s a visual representation:

Mining is the easy part

In most cases, the physical act of moving the ore (rock or clay) from the ground is well understood. Contractors exist, equipment is standardized, and costs are estimable.

What is not standardized is what comes next.

Separation flowsheets are deposit-specific

Impurity removal depends on subtle chemistry. Product specifications vary by customer and end use. Qualification cycles can take years, not months.

To illustrate the level of chemical complexity involved: a separation plant can easily take from 2 to 4 months just to stabilize its system/solution — without producing anything!

And if anything goes wrong, there goes another few months (you get the picture).

This is why two deposits with similar grades can have radically different economic outcomes.

This is where the opportunity lies

Let’s break it down:

If you are a REE miner, producing a concentrate or carbonate, you could: (a) sell your production to China (which already has all capabilities installed for separation), or (b) sell to an intermediary as a ‘tolling’ service. Either path works, but each with its own price.

The REE separation is a chemical-based process, with strong needs for customization to the feed. So depending on the chosen path, projects might not be economically viable.

If you’re a REE miner, you could develop your own separation capabilities. Of course, it’s not easy and it comes with several risks, but if properly done, it can unlock great value

Attention point: (and I apologize for this level of detail, but I must bring this to your attention), Ionic adsorption clays deserve special emphasis, because they illustrate the ‘industry, not mining’ thesis particularly well:

Flow and filtration: Fine clays behave poorly in conventional solid-liquid separation. Settling rates are slow. Filter cakes retain water.

Water management: Low grades mean large volumes of pregnant leach solution. Recycle streams accumulate impurities. Water balance becomes a design-limiting factor, especially in regions with seasonal rainfall or permitting constraints.

Reagent consumption: Ion-exchange leaching may be chemically mild, but it is not reagent-light. Ammonium salts or other lixiviants must be supplied, recovered, or managed at scale. Small deviations in recovery efficiency materially impact operating costs.

Dry stacking is not trivial (this is the big mining risk for IOC): Dry stacking tailings are often presented as a permitting advantage, and it sure can be. But fine clays are notoriously difficult to dewater to stackable moisture contents. Achieving geotechnically stable dry stacks with clay-rich residues is a big engineering challenge. And it’s hard to find individuals with experience in this field.

This is what it means to say rare earths behave like an industry.

None of these issues are fatal, but most of them are industrial problems.

They require pilot data, conservative design margins, and operators who have actually run similar systems, not just designed them on paper.

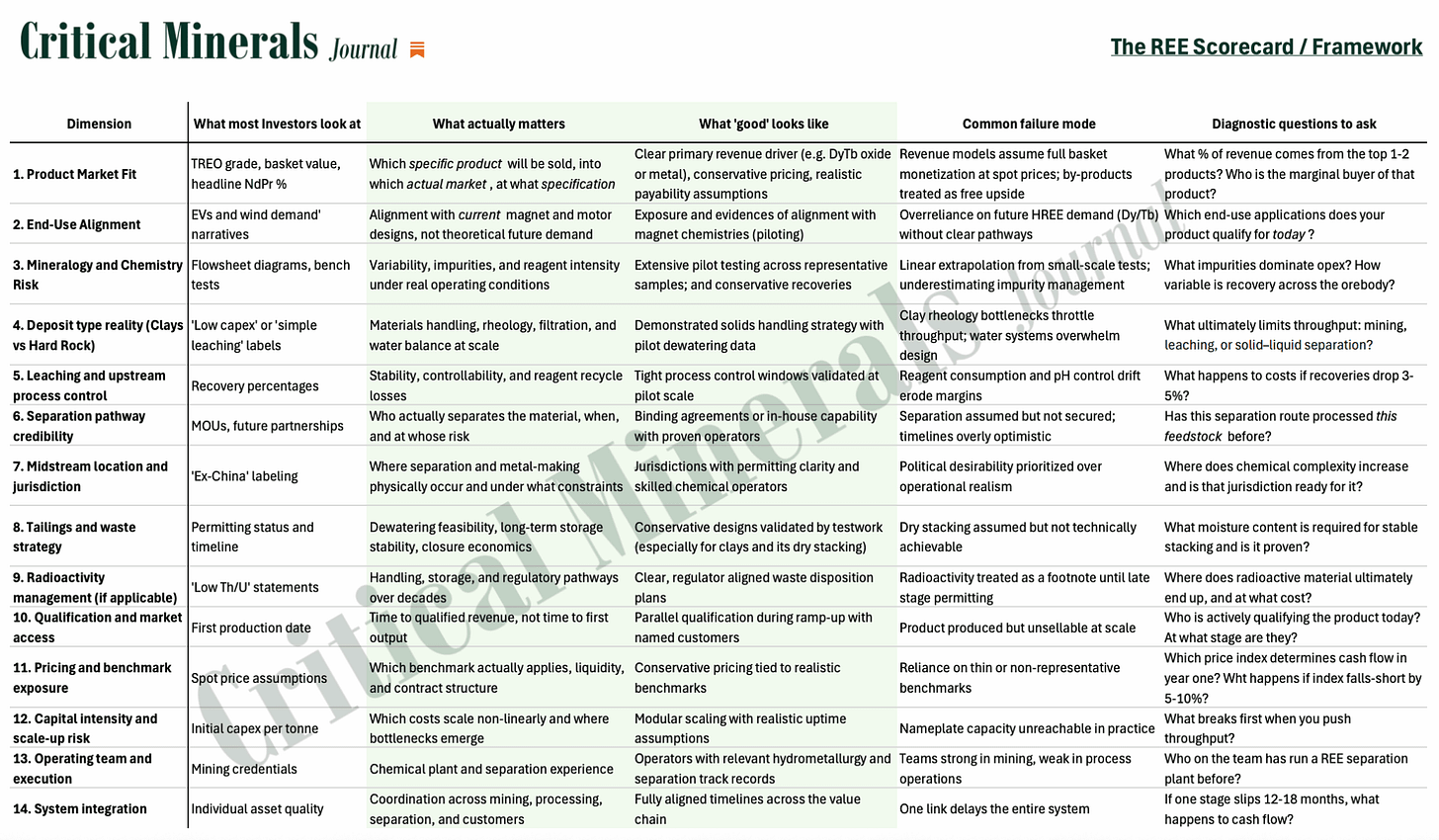

The REE scorecard / framework

I’ve created a practical framework investors can use, reuse, adapt, regardless of deposit type or geography:

Market overview and REE drivers

Why I believe this cycle is different

It’s tempting to frame the current rare earth moment as another commodity supercycle. That framing misses what is actually different:

Industrial policy is now explicit. This has never been seen before in the sector. Governments are no longer neutral observers, and the supply risk just went from ‘theoretical’ to reality.

Magnet demand is resilient. Even when EV adoption slows, permanent magnets remain embedded across multiple industrial sectors (defense, turbines, medical, etc).

Western midstream capacity is constrained. Separation, metal-making, and magnet manufacturing outside China remain limited, and these are not easily or quickly replicated.

The coordination problem is binding. The constraint is not rocks. It is aligning mining, separation, metallurgy, and customers on compatible timelines.

This is why adding upstream capacity alone does not resolve vulnerability, and why so many well-intentioned projects stall.

And on top of that, comes the pricing issue.

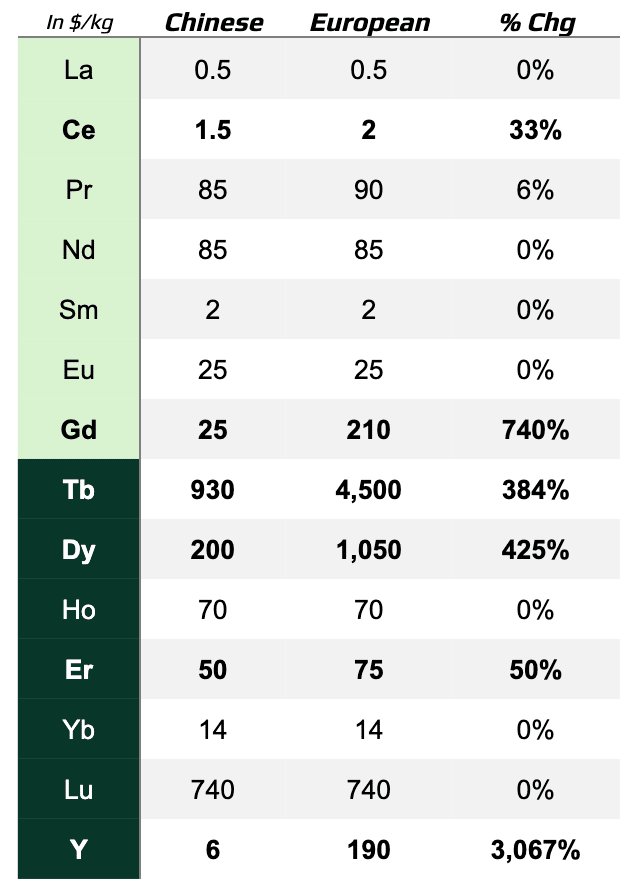

The pricing issue: China vs Europe

Rare earth pricing is often cited as evidence of market inefficiency / distortion, and we tend to agree with that.

Since forever, the only reference of REE prices (either in oxide or metal form) were only quoted in China, with weird characteristics:

No volumes of negotiations

No traceability

Poor transparency and governance

And since April/May, right after China imposed tighter export controls and licensing requirements on certain rare earths and permanent magnets (which is basically the ‘only’ REE product consumed outside of China), a new quotation for REE oxides and metals surged in EU.

Word says the European prices are composed of trading companies and other businesses which had some stockpile of REE, profiting from an opportunity.

And although these prices reflect thin, opportunistic transactions in a stressed market (and should be interpreted as signals of constraint rather than deep, liquid benchmarks) it’s materially different from the official Chinese quotations:

Why are prices so different, you might ask?

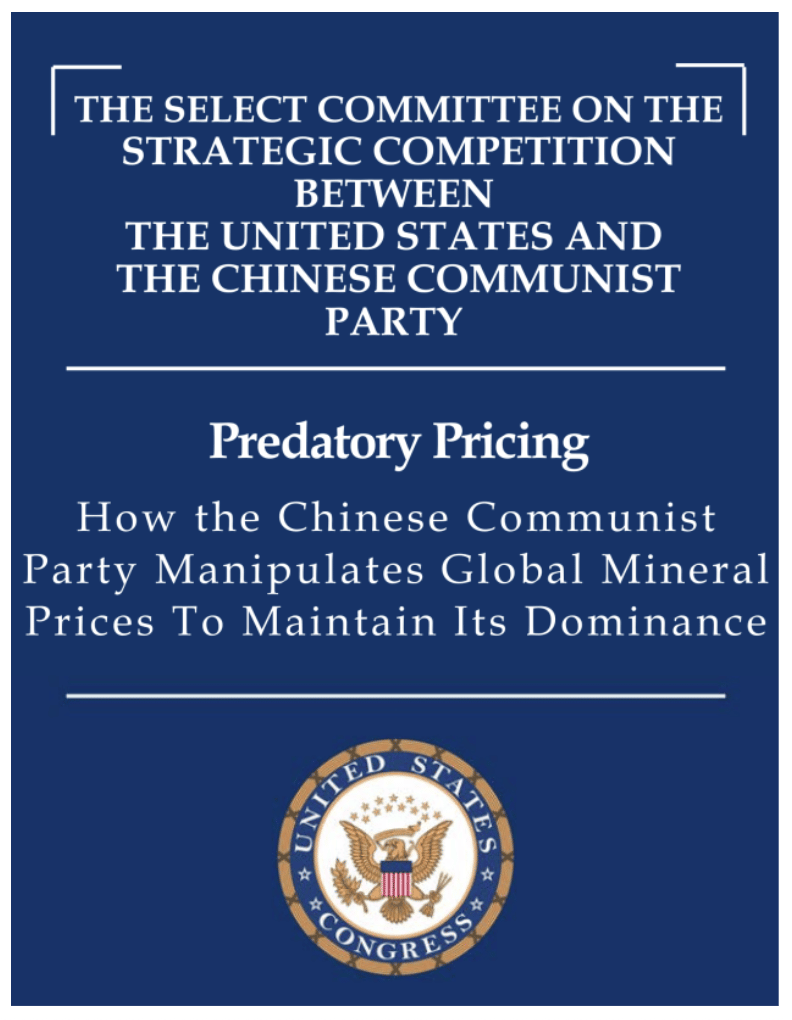

Several reasons, but allegations of market manipulation are among the most cited. Please refer to page 18 of the study developed by the U.S. House of Representatives for further details:

As the saying goes: follow the money!

Evidently, if companies are paying much more for certain REE in the parallel market in the EU, it’s because they are critical. And therefore, these are the ones you should be worried about.

(After all, is there any stronger evidence of a demand constraint than price fluctuation?)

This is important, as it serves as a major tool for you to analyze REE projects. You need to evaluate its basket + content of each element, ignore the non-critical ones. And for the critical, multiply it by its Chinese and EU price references.

By doing so, you’ll have an estimated total revenue as of today.

And going further, if you multiply it by an expected EBITDA margin of 25-35%, you’ll have a solid multiplier of the company and can easily compare peers.

Side note: if the market has such severe price gap between its existing references, it poses a risk for commercial contract (offtakes).

Demand vs forecast: The gap that drives bad investing

Few areas generate more confusion than rare earth demand forecasts.

What the data actually shows (with two leading market intelligence and research firms):

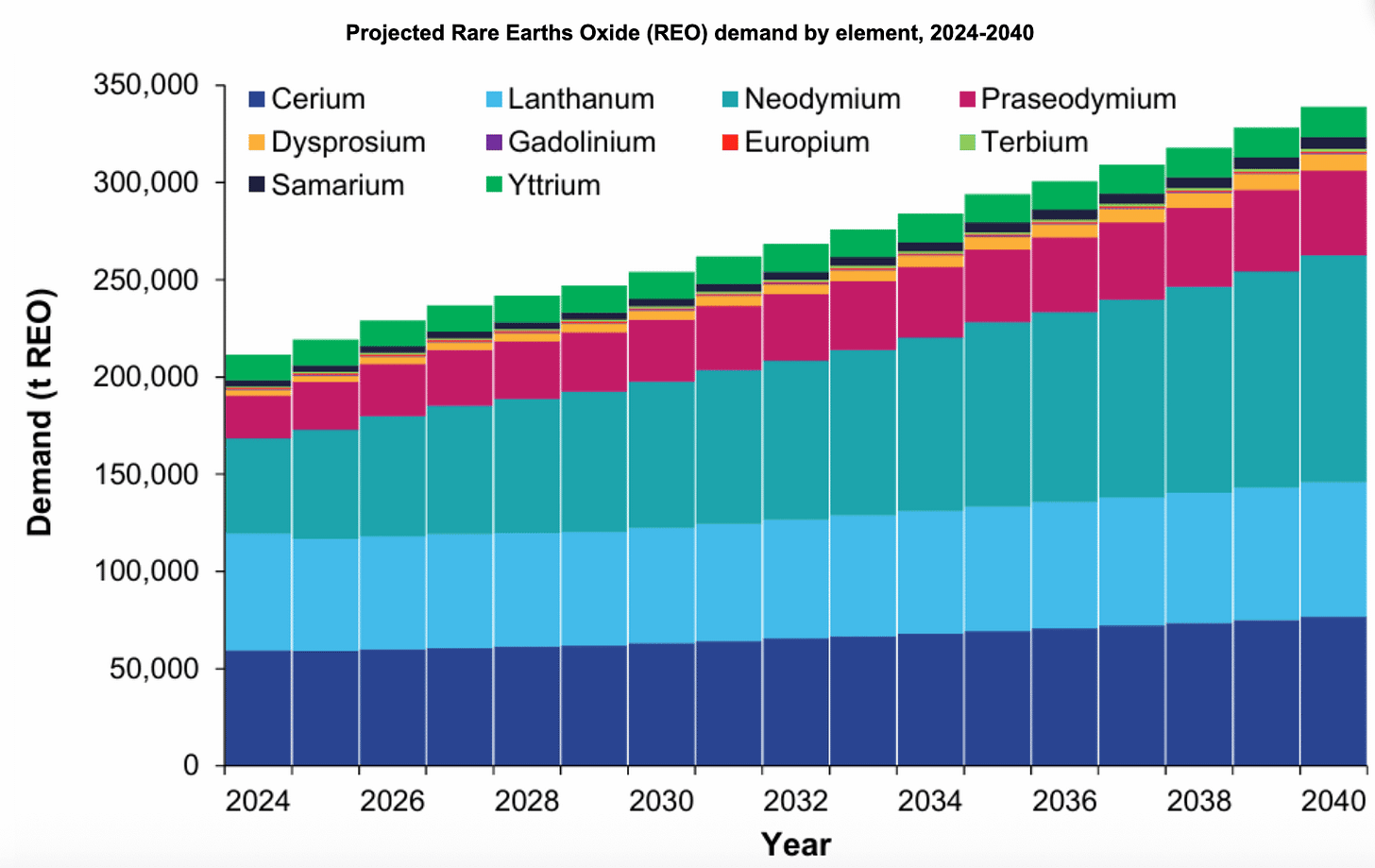

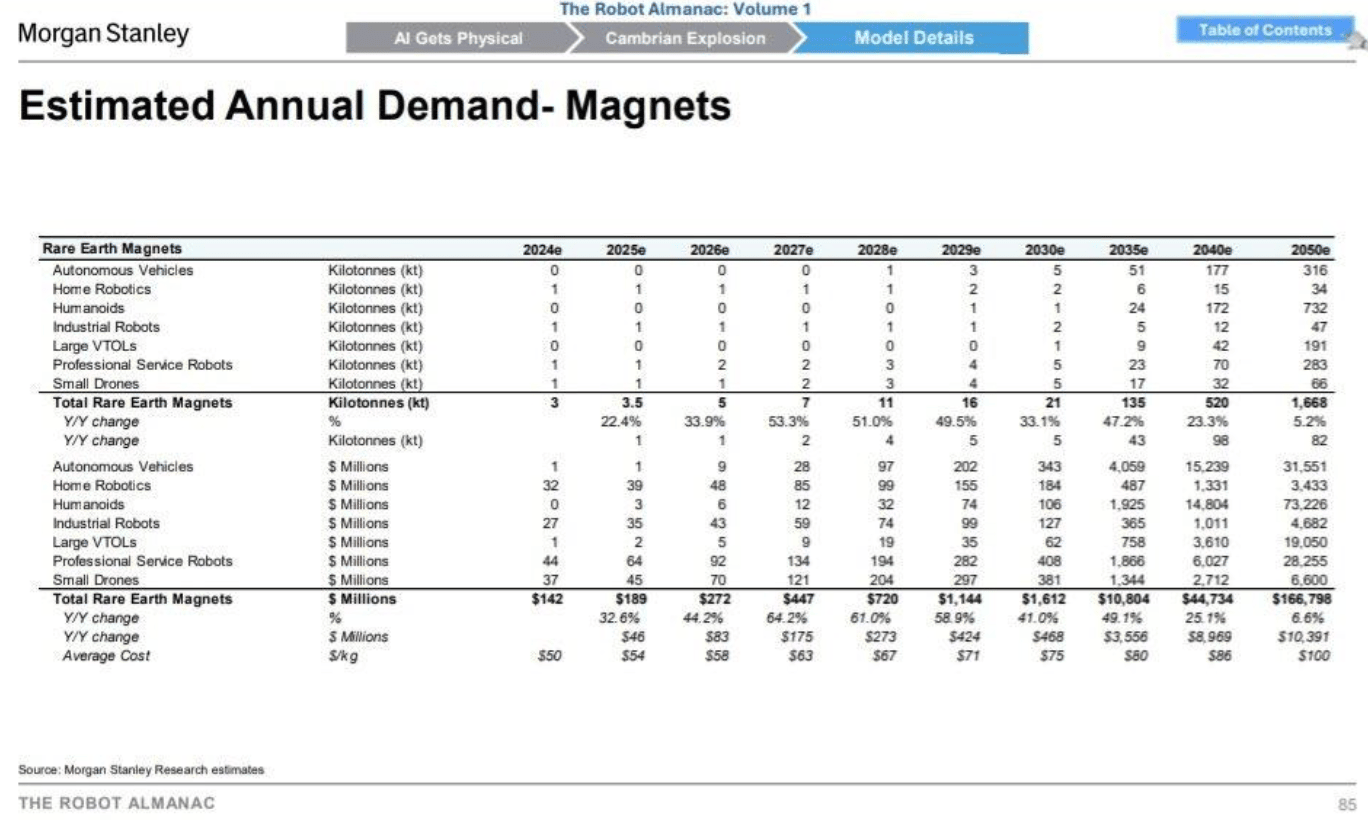

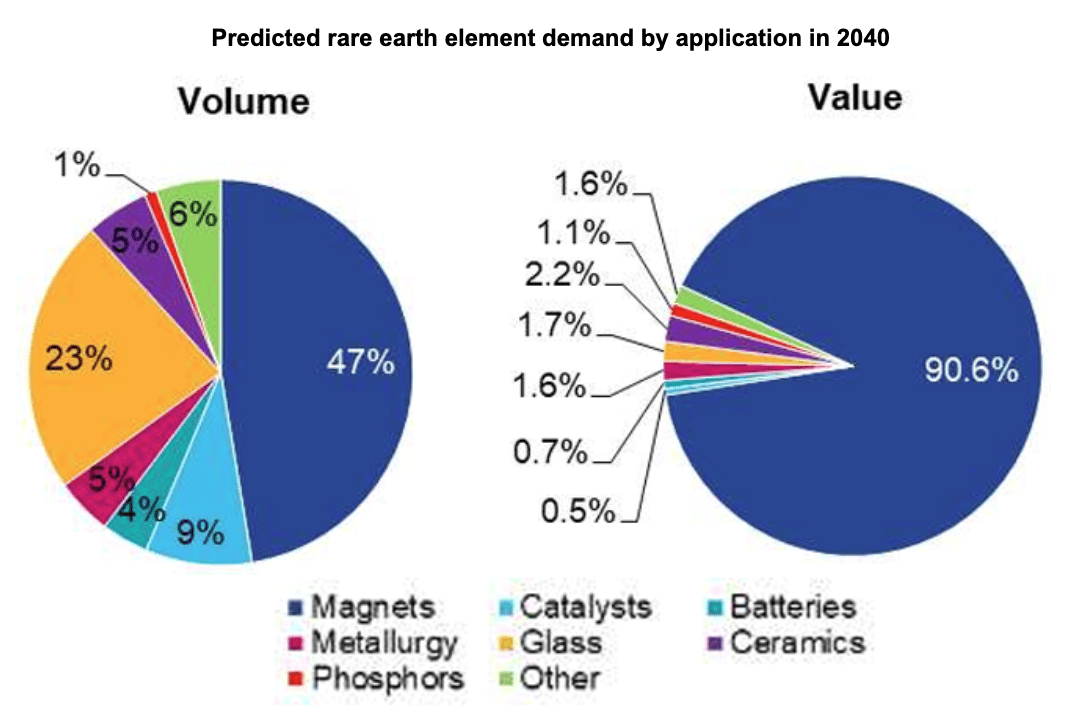

Demand for critical and magnet-related REEs is projected to grow at ~10% CAGR for the next 15 years

While magnets’ demand increases by +20% CAGR for the next 10 years

REE demand drivers come from:

Electric vehicles and hybrid drivetrains

Robotics and automation (industrial, service, humanoid)

Aerial mobility and drones (cargo, passenger, defense)

Defense, aerospace, and national security systems

Wind energy and power generation (especially offshore wind)

Consumer electronics and precision devices

Industrial motors and high-efficiency machinery

Catalysts, optics, and specialty chemical applications

The list below is not exhaustive, but illustrates how demand concentration, not abundance, drives strategic relevance:

Dysprosium (Dy): high temperature coercivity additive for NdFeB magnets (EVs, industrial motors)

Terbium (Tb): magnet additive for thermal stability; phosphors (lighting/displays)

Yttrium (Y): phosphors; advanced ceramics (YSZ); specialty alloys and materials

Neodymium (Nd): NdFeB permanent magnets for EV motors, wind turbines, industrial motors, electronics

Praseodymium (Pr): NdFeB permanent magnets (NdPr alloys); specialty glass and pigments

Gadolinium (Gd): MRI contrast agents; specialty alloys and materials

Cerium (Ce): glass polishing powders; automotive and industrial catalysts; glass additives

Samarium (Sm): SmCo permanent magnets (high-temperature, defense/aerospace); catalysts

Lanthanum (La): FCC catalysts in oil refining; optical and high-refractive glass; legacy NiMH batteries

Europium (Eu): red phosphors for lighting and displays

Erbium (Er): fiber-optic amplifiers (EDFA)

Holmium (Ho), Thulium (Tm), Ytterbium (Yb), Lutetium (Lu): lasers, medical imaging, specialty industrial applications

Additionally, we’d highlight the REEs uses by 2040:

The framework to track REEs demand picking up is:

Magnet output capacity additions (new plants, especially in the Western)

Qualification announcements by OEMs

Actual contract volumes (offtakes), not nameplate capacities

Demand is real, but it is not on autopilot.

How to avoid the REE trap

Where investors get it wrong

Capital misallocation in rare earths follows a familiar pattern:

Overinvestment in upstream projects with weak downstream integration

Underinvestment in separation, metallurgy, and qualification

Disappointment when production does not translate into cash flow

This is not malice or incompetence, it’s just a consequence of applying the wrong mental model:

Mining logic favors optionality and scale

While industrial logic favors reliability and specification

Remember: REEs are closer to the industrial logic, but with the caveat of material handling.

How investors should think

Rather than looking for ‘the next rare earth mine’, investors should ask strategic questions such as:

What exact product will this project sell?

In the case of concentrate / carbonate, where does separation actually happen?

What impurities drive cost and risk?

Who is the buyer and have they qualified it?

How sensitive is economics to recovery losses?

What scales poorly at higher throughput?

Which benchmark underpins pricing?

What breaks first if timelines slip?

And of course, use the scorecard / framework

Closing thoughts

Rare earths are not scarce because the earth lacks them.

They are scarce not because they are absent, but because they are not found individually in nature, and turning them into usable products requires precision, patience, and coordination across multiple industrial domains.

Investors who understand that will stop asking who controls the rocks, and start asking who can actually deliver the molecules with confidence.

That shift, more than any headline, is where durable insight begins..

Thank you for reading.

In markets driven by geopolitics, foresight is power. If you found it valuable, share it with a peer who needs the same edge (or keep it close and use it to your advantage!)

Hope to see you in the next issue of the Critical Minerals Journal

See you next time, Gustavo

Disclosures

This issue was written by Gustavo from Critical Minerals Journal, and edited by Stefan von Imhof

This issue was sponsored by IDX

Alt Assets Inc has no interests in any companies or minerals mentioned in this issue

This issue contains no affiliate links

Great article. However you forgot to mention the radioactivity profile. China beats almost every other project in this area because of their ion clays. Chinese extraction refining and processing leaves a much lower environmental footprint without Radioactive tailings.

Brilliant and insightful